|

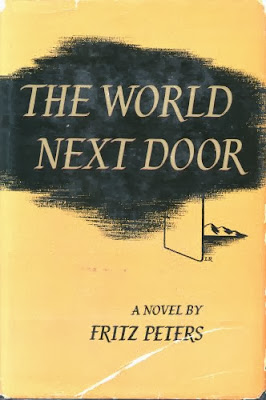

| New York ; Farrar Straus, 1949 |

When he arrives, David doesn't know where he is and vacillates between believing he is an American spy being protected by the British and being a prisoner of war being held by the Nazis. It's possible both are true and he can't understand why he isn't being protected from the Nazis.

It's 1947 and it soon becomes clear to the reader, that David has been taken to a psychiatric ward. He doesn't understand why he's there and his agitation and inability to do as he is told lands him in the pack unit, where patients are wrapped tightly in wet sheets, a 'sheet pack', in an effort to calm them down.

Upon his arrival to the unit, he believes, no, he knows that he is Jesus Christ. He has the cigarette-burn stigmata to prove it. What he wants more than anything is for someone—anyone to believe him and to believe in him. When one of the night attendants attempts to rape him, he creates an unbelievable scene and manages to get the priest and the doctor to come to the ward. There he makes a convincing argument for a psychiatric patient's rights. Of course the doctors are going to believe the attendants—the patient is obviously crazy. What kind of power does that put into the hands of the staff? He lives in constant fear of saying the wrong thing. Will it make them angry with him? Will he be punished? There is a powerlessness that is all encompassing. Even as his mind begins to clear, David doesn't trust his own thoughts. David describes being in love with attendants, doctors or other patients who are nice him. He later realizes that it isn't love that he feels, but a sense of gratitude for the gentle way they treat him.

Mr. Newton suggests that David's accusation against the attendant might stem from his own homosexuality. There was also a similar claim in David's file from the army where a general "tried to get funny". David is clear that he had slept with another man in his 20s but is not a homosexual. "I was in love with him, that's all." David's mother had shared with Mr. Newton these earlier experiences "as a possible cause of [his] illness." What's truly at the heart of his illness is a spiritual and moral collapse brought on by an inability to reconcile his spiritual beliefs with the horrors he witnessed during World War II.

The World Next Door is a fictionalized version of the author's own experiences and shows the horrors of psychiatric treatment during the 1940s and 1950s, including the use of wet sheet packs, insulin shock and electro-shock therapies. It was very well received upon publication and shown a bright light on psychiatric hospitals and psychiatric practice broadly, and issues within Veteran's Administration hospitals in particular. Mary Jane Ward, the author of The Snake Pit (1946) wrote the single critical review for The New York Times. She called it 'sincere' and then proceeded to pick it apart. One wonders if this isn't a case of feeling like another author was muscling in on her turf. The book had a significant enough impact that you still find it in medical libraries across America, unusual for a novel. The World Next Door was excerpted in Harper's Bazaar, released in several English editions, translated into both French and German, and was performed in France as a radio play.

Bibliographies & Ratings: Cory (III); Garde (OTP, a***); Mattachine Review (III); Young (3021)

![The World Next Door by Fritz Peters ; FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: [1] New York : Harper's Bazaar, July 1949 (excerpt) [2] London : Victor Gollancz, 1950 [3] New York : Signet/NAL, 1950 [4] Le Monde à Côté, French translation by Amélie Audiberti, Paris : Éditions Denoël, 1953 [5] Die Welt Nebenan, German translation by Utta Seifert-Roy, Hamburg : P. Zsolnay, 1956 [6] London : Victor Gollancz, 1967 The World Next Door by Fritz Peters ; FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: [1] New York : Harper's Bazaar, July 1949 (excerpt) [2] London : Victor Gollancz, 1950 [3] New York : Signet/NAL, 1950 [4] Le Monde à Côté, French translation by Amélie Audiberti, Paris : Éditions Denoël, 1953 [5] Die Welt Nebenan, German translation by Utta Seifert-Roy, Hamburg : P. Zsolnay, 1956 [6] London : Victor Gollancz, 1967](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgHC8GJDTCnn2q_JPEuR13aaQzCS64gXcJTNbNZEQI60GMvu8TrE1EPI29xwiMrao8RL9xd0txHVOnBbgTgrh7djjj6C8_Hic_X4NuVbi_QkOfAsRA_8XYjs0mLtxgf3yFY9xRJxhvrMAo/s640/Peters_WorldNextDoor_combo.jpeg)