|

| Swimmer (1866) John La Farge (American, 1835-1910) Watercolor 32.5 × 28.2 cm (12 13/16 × 11 1/8 in.) Yale University Art Gallery |

Monday, February 28, 2022

Swimmer by John La Farge

Friday, February 25, 2022

Fritz Peters, Early LGBTQ Literary Icon, Coming to Screens and Bookshelves in New Rights Deal

|

| Fritz Peters c.1965 Collection of Edward Field |

Fritz Peters, Early LGBTQ Literary Icon, Coming to Screens and Bookshelves in New Rights Deal

By Matt Donnelly

Variety : February 23, 2022 12:32pm PT

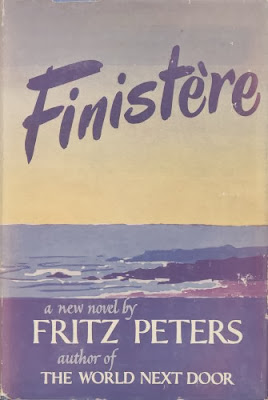

"Peters’ most notable work was his second novel, “Finistére.” It is regarded as one of the first gay-centered novels to come out of the era not concerning WWII. It details the adolescence and homosexual encounters of its main character and is said to be inspired by Peters’ own life. Acclaimed by Vidal, it received an unheard of first-run printing of 350,000 copies, according to his estate. It is also the first up for adaptation, with a screenwriter to be announced imminently."

Sunday, February 20, 2022

Finistère by Fritz Peters

|

| New York: Farrar, Straus, 1951 |

Peters' second novel focuses on the tumultuous adolescence of Matthew Cameron. As Gore Vidal noted in his much quoted book review in The Saturday Review of Literature (Murder of Innocence, v.34:no.8, p.13, February 24, 1951), the first third of this book lays out the many betrayals experienced by young Matthew. The middle third lays out the story of Matthew's relationship with Michel, and the final third follows the rapid disintegration of Matthew's world.

Tobias Schneebaum (1922-2005), in his introduction to the 2003 re-release of his 1979 work Wild Man (University of Wisconsin Press), discusses the reception of his early work's gay themes and the ways in which authors, such as Gore Vidal and Fritz Peters conformed to expectations of publishers of the time. In 1965, a new edition of the 1948 novel The City and the Pillar was released "in order to return to it the strength, the temperament and the animus that Vidal had wanted in the first place." Schneebaum further states that Fritz Peters was forced by his editor to change his original happy ending for Finistère to "an ending that was tragic, to conform with contemporary ideas concerning what interested the public and what was obscene."

It is the summer of 1927. Thirteen-year-old Matthew's parents are divorcing and he and his mother are relocating to Paris. She has decided Matthew is too attached to her and to Scott Fletcher, a close friend of the family so Matthew is to be enrolled in the boarding school, St. Croix École des Garçons. Soon after Matthew's arrival at the school, André, a classmate, shares some dirty pictures with him and they become friends. The headmaster approves of them sharing a room and before long they are having a sexual relationship—a relationship about which Matthew feels quite guilty.

While with his family at the Christmas holiday, Matthew meets his mother's new 'friend', Paul Dumesnil. While Paul makes an effort to include him in conversations and activities, Matthew now feels like an outsider. As a condition of his parents divorce, Matthew isn't permitted to see his father until he reaches age 16. His father effectively disappeared from his life, and now he feels he is losing his mother as well.

By the following fall 1928, his mother marries Paul. Scott, whom Matthew has idolized for years, has become engaged to Françoise. Scott, who had always been available to him is now focused on his relationship with Françoise and seems to have no time for him. Françoise seems to be the only adult who recognizes Matthew's attachment to Scott for what it is.

After a summer with his family, Matthew returns to school in the fall of 1929, to discover that André has gone, having moved to a different school. Alone and without support from any of his relationships, he feels lost. Michel Garnier, a new athletic coach, has joined the school and upon the boys' first outing for a swim in the Seine, Matthew swims too far and seems to give in to the current pulling him under. The relationship with Michel begins after he saves the drowning Matthew and helps to nurse him back to health. Their relationship brings Matthew back to life, feeling true love for the first time without all of the guilt he felt about his relationship with André. However, Matthew is innocent and this idealized first love can't insulate him from the cruelty of the world or of the adults in his life.

It is no surprise that the ending of a gay novel from this time is likely to end tragically—most (but not all) did. As might be surmised by the many editions over the years, Finistère was popular among gay men despite the ending. The central message of the novel isn't that gay people are bad, or in this case, the problem isn't that Matthew is gay. The problem is that the adults in Matthew's life are incapable of supporting him.

Matthew's Happy Ending

![Fritz Peters correcting galley proofs of his second novel, Finistère November 27, 1950 [cat 3119-0007] Private Collection Fritz Peters correcting galley proofs of his second novel, Finistère November 27, 1950 [cat 3119-0007] Private Collection](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/a/AVvXsEi7Da54P20PmDNTxjla21DeD-x54yQNrY1oqODA-f-1d1TsB7V2c2C6Ebz_0PGir1A0tBGa1kXcv0BPpLE6nf7kgaSswl7PADNKTsRLNyfBDQPcQ2IaBxS7yNMj0eKvQJG3-YWeCM06_8pCKFgUPDXx_UMFgZBnmtqrlC8klxqq-7CmjRJRnwGEipMA=w320-h252) |

| Fritz Peters correcting galley proofs of his second novel, Finistère November 27, 1950 [cat 3119-0007] Private Collection |

Columbia University Libraries announced in the Our Growing Collections column in Columbia Library Columns (v.13:no.2 1964:February, p.55) that "Mr. Fritz Peters has presented the manuscript of his novel, Finistère, published in New York in 1951." Interestingly it was listed under the section for medical library gifts. It is now housed in Columbia's Rare Book and Manuscript Library within the collection, General Manuscripts, 1789-2013. The type-written manuscript with minor changes in ink follows the published work, including the tragic ending.

If there was an original happy ending to Finistère, it appears to have been lost to history. What might Matthew's life have looked like, had Fritz Peters been free of the cultural and moral restrictions of mid-twentieth century American publishing?

Bibliographies & Ratings: Cory (IV); Garde (Primary, **); Mattachine Review (IV); Young (3019/3020,*)

Bibliographies & Ratings II: Austen (174); Gunn (American 54a); Levin (121)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

![Finistere by Fritz Peters ; TOP ROW FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: [1] London : Victor Gollanz, 1951 [2] New York : Signet/NAL, 1952 [3] Fin de la Tierra, Spanish translation by A. S. Glanz, Buenos Aires : Editorial Dintel, 1953 [4] The World at Twilight, New York : Lancer Books, 1964 [5] New York : Lancer Books, 1966 [6] London : Victor Gollanz, 1966. ⸻ BOTTOM ROW FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: [7] New York : Lancer Books, 1968 [8] London : Panther, 1969 [9] Los Angeles : Seeker Press, 1985 [10] New York : Plume/NAL, 1986 [11] Vancouver : Arsenal Pulp Press, 2006. Finistere by Fritz Peters ; TOP ROW FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: [1] London : Victor Gollanz, 1951 [2] New York : Signet/NAL, 1952 [3] Fin de la Tierra, Spanish translation by A. S. Glanz, Buenos Aires : Editorial Dintel, 1953 [4] The World at Twilight, New York : Lancer Books, 1964 [5] New York : Lancer Books, 1966 [6] London : Victor Gollanz, 1966. ⸻ BOTTOM ROW FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: [7] New York : Lancer Books, 1968 [8] London : Panther, 1969 [9] Los Angeles : Seeker Press, 1985 [10] New York : Plume/NAL, 1986 [11] Vancouver : Arsenal Pulp Press, 2006.](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/a/AVvXsEj28t2kAu1uP3Mx13EwoLZ0rCmtkxdUq0cu-UVUiRtbWdzRGaWy-E52G2f4x5ZBUH-ST5a2oW4-bzcOxEG15AEQ0q7ostfeH_UaR5qB8pSjpXi7L67GdrNHs9IUwFjage5y4VZMfkZBg-5dCd9ljoLMbqTSs0Fhwsjrm7MbRLMyv4XVYSo4TUx0zKte=w640-h325)