|

| Jean Desbordes (c.1928) Jean Cocteau (French, 1889-1963) Ink wash, watercolor and pastel on paper |

Tuesday, July 11, 2023

Friday, June 23, 2023

Why Such a Strong Reaction? : Mary Jane Ward's Review of Fritz Peters' The World Next Door

|

| TOP ROW: The World Next Door, New York : Farrar, Straus, 1949 with author, Fritz Peters. BOTTOM ROW: Author, Mary Jane Ward and her novel, The Snake Pit, New York : Random House, 1946. |

Reviews of The World Next Door often referenced and compared it to Mary Jane Ward's landmark The Snake Pit from 1946 due to its focus on the patient experience within a psychiatric hospital. While some reviewers suggested that it held its own against the standard-bearer of psychiatric novels, others thought that it was in fact superior. When The New York Times Book Review published its review of The World Next Door penned by Ms. Ward it became the talk of the literary world.3, 4 It was much discussed because it was so out of step with the consensus view of the work. In order to understand the source of this scathing review, one must first try to understand Mary Jane Ward's experience publishing her own novel based on her stay in a psychiatric hospital.

|

| Excerpt from Nightmare Revisited, Mary Jane Ward's review of Fritz Peters' The World Next Door.4 |

For all of the issues that Ward hoped to change in psychiatric care, she saw those doctors and staff providing treatment as generally good people trying to do good work. Peters' novel provides insight into the male experience, and the experience at a military hospital in the post World War II years in particular—a very different situation than the one Ward described.

Unlike, Ms. Ward, Fritz Peters appeared to become an overnight success—blurbed by major authors and also drawing attention to the shortcomings of psychiatric care at that time. The World Next Door, based on Peters' own experience, sees its protagonist, David Mitchell admit during the course of his treatment that he had a previous homosexual experience. Because patient records were available to staff of all levels on the ward, it became common knowledge. This knowledge was used against him by ward staff, culminating in a sexual assault. But because the word of a psychiatric patient can't be trusted, his accusation wasn't believed by the doctors.

Did Mary Jane Ward simply not find plausible the idea of staff behaving in this way? Or did Ward find Peters' characterization of hospital staff as not only unfeeling but as potentially sexually predatory a threat to all of the work that she had done in recent years to improve the patient experience? Was this simply a case of sour grapes for Peters' writing in a genre that she had dominated? Or was it more about the relative ease with which the literary establishment welcomed Peters' work after Ward had struggled for years to get published? Was his relative ease of being published down to sexism? One thing is for sure, Peters certainly struck a nerve.

Note

This post is meant to highlight an anomalous review of Fritz Peters' The World Next Door, while giving the reader a sense of how the book was generally received and what Peters' literary future was perceived to hold. Mary Jane Ward's The Snake Pit is an extraordinary work and remains a favorite of early Cold War era psychiatric novels. Both authors and their novels, which offer different perspectives on a common theme, are well worth a read.

1 Bixbi, G. (1980, Win.). Blurbs: Welty on Fritz Peters. Eudora Welty Newsletter, 4(1), p.2-6

2 Babcock, F. (1950, Jan. 1). Among the Authors. Chicago Daily Tribune, p.F6.

3 Kilgallen, D. (1949, Nov. 3). Voice of Broadway. Olean Times-Herald (Olean, NY), p.18.

4 Ward, M. J. (1949, Sept. 18). Nightmare Revisited. New York Times Book Review, p.6.Friday, June 9, 2023

Wednesday, May 24, 2023

The Welcome by Hubert Creekmore

|

| New York : Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1948 |

Don returns home to Ashton, Mississippi after having left for New York and struggling there in the Depression of the 1930s. His mother needs him to care for her after his father's death and now that he's back, wants to monopolize his time to the exclusion of his friends and love interests. His best friend, Jim, had married Doris before Don left Ashton, thus closing off their relationship. Upon his return, unresolved feelings and societal expectations come to the fore. Can Don and Jim simply be friends after having loved one another in the past? Are they still interested in being friends? How do they handle the expectation to marry and have children? Is it fair to any woman for a gay man to marry her?

Set during the 1930s in a small town, it is an environment where everyone knows everyone else's business while everyone simultaneously believes that their struggles are their own inner secret. Creekmore highlights the significant social changes during the interwar years and how various characters have adjusted at different speeds and to different levels. What do men's friendships look like? What is an acceptable level of closeness between men? What is the role of women? Must they marry? What does it say about them if they don't.

Tray, a childhood friend to both Don and Jim is seen by some as basic—certainly not among the elite of the town. He, on the other hand, accepts everyone for who they are and is depicted as both the everyman as well as the sage advisor to both of his friends. Tray offers these wise words that speak to the theme of the book and speak to the individual struggles of all of the characters: "If only people could forgive each other for loving."

Written in close third person, the reader comes to understand how each character thinks of their place in the world and the few options they perceive themselves to have. Particularly in Part One, as the author introduces the characters, he uses that close third to excellent effect by focusing a chapter on a particular character, introducing another character during the action of the chapter who then leaves by the end only to show up as the focus of the subsequent chapter. It's a skillful way of creating the community of Ashton and assisting the reader in understanding the characters' relationships to one another.

Creekmore doesn't rely on simple resolutions either—such as killing off one or both of the gay protagonists which might have been more typical of the time. Likewise he also doesn't give us a happily ever after ending. The lives he presents are complex and allowing the characters to be complicated, with difficult choices to make, results in a story that feels real— both relatable and believable.

|

| Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, 2023 |

After being out of print and virtually unfindable for decades, Phillip Gordon has shepherded a 2023 reissue through The University Press of Mississippi to which he has also provided an introduction. Gordon places The Welcome within the context of what little is known about Creekmore's life, particularly his friendship with Eudora Welty. For those interested in early gay literature, especially as regards life in the rural south, Mr. Gordon has done the world a great service by reviving this lost gem.

Bibliographies & Ratings: Cory (IV); Garde (Primary 73, **); Mattachine Review (IV); Young (848,*)

Bibliographies & Ratings II: Austen (116); Gunn (American 41a); Levin (80); Slide (15)

Thursday, May 11, 2023

Ilja (Portrait of Karl Edvard Holmstrom) by Gosta Adrian-Nilsson

Wednesday, April 26, 2023

In Memoriam by Alice Winn

|

| New York : Knopf, 2023 |

The author uses a variety of forms, including letters and issues of the school newspaper, The Preshutian, to follow Gaunt, Ellwood and their friends through the actions of the war, including the horrors of the Somme and the deaths of many.

Boarding school novels set in the 1920s often discuss the 'Old Boys'—those former students who fought in World War I and sometimes return for cricket matches against the current students. Winn has flipped this by constructing a boarding school novel that highlights the youth and excitement of the students but then follows them into the war. What is glorified in bravery by the school and its students is a horror laid bare through their experience of the war.

Wednesday, April 12, 2023

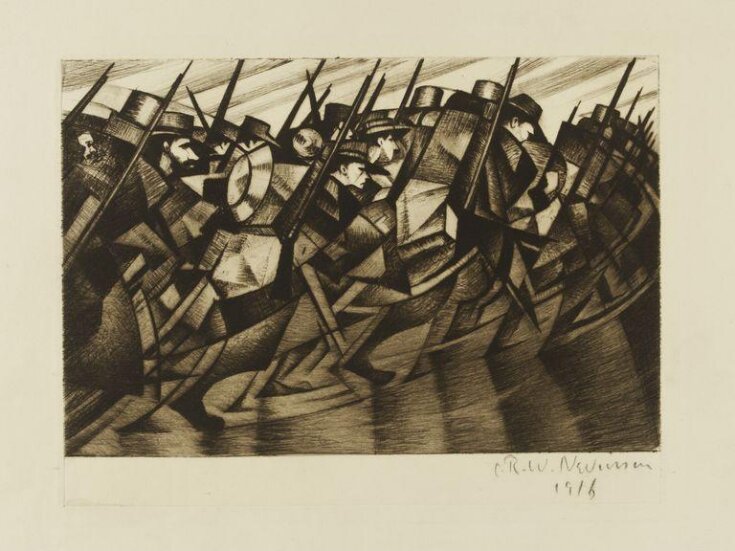

Returning to the Trenches by Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson

|

| Returning to the Trenches (1916) Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (English, 1889-1946) Etching and drypoint 13.3 x 20.1 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum |

Tuesday, March 28, 2023

Undue Fulfillment* by Kathleen Coyle

|

| New York : William Morrow & Co., 1934 |

"It is not a crime to be a poet."

"No ... it places one on a plane where crime is so sublimated that it has another name."

In the vein of Birabeau's Revelation (1930), Undue Fulfillment is focused on a mother dealing with her son's relationship with another man. Although in this instance we hear from the son, the primary focus of the action is on the mother and her thoughts and feelings about her adult son's life and whether she has been successful at raising him.

Agatha's late husband served in World War I and having struggled since his years of service committed suicide while their son Lawrence was still young. As Lawrence grew up, Agatha held him close—too close she decided. For fear that he would not be able to disengage from his relationship with his mother enough to find a wife, Agatha returns to the convent in Ireland where she grew up, leaving Lawrence their home in Paris.

Upon hearing that Lawrence's relationship with Lena has ended, Agatha travels to Paris in hopes of bringing the two back together. Upon meeting with Lena, Agatha learns the reason for the split—Lawrence's new close relationship with Cesar Brak, a poet from Lawrence's parent's generation. While the relationship is not labeled as gay or homosexual, it is clear from what is said (and what is not said) that the relationship is sexual.

Structured around Agatha's connection to the convent and her brother Owen being a monk, there is a strong religious morality to the story. Lawrence's father who committed suicide was named Judas and appears to serve as a symbol of betrayal of his wife and child. This is juxtaposed with Cesar Brak and his generation having served in the war which was so devastating that it is hard to reconcile with the existence of any god. This is a philosophical novel about the nature of motherhood and how we reconcile our spiritual life with the challenges of being human in an ugly world.

* Also published under the title Undue Fulfilment by Ivor Nicholson & Watson Ltd., London (1935).

Bibliographies & Ratings: Cory (IV); Garde (P 50 *); Mattachine Review (IV); Young (839)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

%20Henri%20Cartier-Bresson%20%201935%20gelatin%20silver%20print.png)

%20(1911%E2%80%9312)_67x47cm.jpeg)