|

| Langston Hughes (1927) Winold Reiss (American, 1886-1953) Pastel on illustration board 54.9 x 76.3 cm. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution |

Friday, February 21, 2020

Langston Hughes by Winold Reiss

Wednesday, February 5, 2020

The New Negro : The Life of Alain Locke by Jefferey C. Stewart

|

| New York : Oxford University Press, 2018 |

2018 National Book Award

2019 Pulitzer Prize

Alain Locke was born into a Black Victorian family in Philadelphia in 1885. Stewart masterfully lays out the complexity of Locke's life through which he must balance his desire to be a successful black intellectual with his gayness.

After completing his education at Harvard where he was generally accepted, Locke has his first serious experience with racism while a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford when the scholars from the southern United States refuse to board in the same college as him and intentionally leave him out of group activities. Locke does make some friends though and escapes to mainland Europe, to Paris and Berlin, where his race is not an issue and he is free to explore his sexuality in a more open environment. His escape however proves detrimental to his scholarship and he fails to receive his degree from Oxford.

With the idea of completing his studies in Berlin, he asks his mother (with whom he maintained a close relationship) to join him there. When Archduke Ferdinand is shot, the Germans close the border and they are temporarily trapped. Although U.S. officials do work to evacuate them, due to their race, they are not a high priority. Once back in America, he takes a teaching position at Howard, but quickly realizes that without a PhD he won't achieve the standing and influence he desires. While on leave from Howard he completes his doctorate at Harvard. By this time, with the election of Woodrow Wilson—the first southern president elected since Reconstruction—race becomes more of a problem for Locke, particularly with segregated housing districts.

After completing his PhD, Locke decides to vacation in Europe and while visiting Berlin during the Weimar era, takes in some of the Modernist theater of the time. This presentation in the arts of the lives that the artists are living resonates with Locke and was a confirmation of the sort of artistic movement he envisioned for black Americans; what we would later know at the Harlem Renaissance.

Locke had been friends with several writers that are now known as part of the Harlem Renaissance; Claude McKay and Jean Toomer in particular. McKay frequently introduces Locke to new young writers, particularly young men, whom Locke encourages and mentors to a degree. The Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP, served as the primary outlet for these writers' work but simply accepted or denied work for publication instead of bringing new writers along with the sort of encouragement that Locke felt was necessary to create a movement. This was personal for Locke since he had experienced this himself with articles he submitted to the publication that didn't get him the attention from the editor that he felt he deserved.

By the time Locke returns from a trip to Europe and Egypt in 1924, Robert Kerlin has released Negro Poets and Their Poems in connection with The Opportunity, the publication of the National Urban League. This was the kind of thing that Locke had envisioned, a vehicle to promote the new writing in this movement of black writers. Charles Johnson, the editor at The Opportunity, like Locke, saw the connection between European modernism and African American poetry and theater and hoped to promote the arts within the pages of the magazine.

|

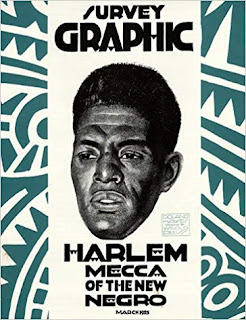

| 'The Harlem Number' Survey Graphic : March 1925 |

While Locke emphasized his vision for this new movement at the dinner, he emphasizes the importance of leaving old forms behind, thus alienating some the attendees. Jessie Redmon Fauset was the literary editor at The Crisis and had herself just published a novel in the style that Locke had so easily dismissed. Locke underestimated the power of Fauset and The Crisis in general however. The following day, newspaper articles describing the event omitted Johnson and Locke entirely, focusing primarily on Fauset and her new novel.

Although the dinner didn't get Locke and Johnson the sort of publicity they hoped, Paul U. Kellogg, the editor of Survey Graphic was in attendance and this led to the next opportunity for them to promote their envisioned movement. Each issue of the magazine focused deeply on a topic and Locke suggested to Kellogg the idea of an African American issue focused on the arts and featuring commentary from leading voices. Locke acted as silent editor of what would be later known as the Harlem Number. While it was a success at promoting the movement, Locke's involvement continued to be out of view.

Before the Harlem Number was published however, there were already thoughts of expanding the concept into a larger work. Albert Boni had recently started a publishing house with his brother and inquired about republishing the content of the magazine with new material in book form, also edited by Locke. This would become The New Negro: An Interpretation, published in 1925 and solidified Locke's critical role in promoting the authors and writings of what we now know as the Harlem Renaissance.

Tuesday, January 28, 2020

Jean Cocteau a l'Epoque de la Grande Roue by Romaine Brooks

|

| Jean Cocteau à l'Époque de la Grande Roue (1912) Romaine Brooks (American, 1874-1970) Oil on canvas 251 x 135 cm Musée National d'Art Moderne on loan to Musée Franco-Américain du Château de Blérancourt |

"The painting originally included a pair of women on the balcony, standing apart from Cocteau; she cut the painting in half, making the Eiffel Tower the focus of the composition. Brooks would later delight in quoting [W. Somerset] Maugham, who predicted when the painting was first exhibited that Jean Cocteau would be remembered only because of Romaine Brooks's portrait of him."

Jamie James

Pagan Light : Dreams of Freedom and Beauty in Capri

New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2019

p.166-7

Thursday, January 16, 2020

Pagan Light : Dreams of Freedom and Beauty in Capri by Jamie James

|

| New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2019 |

Pagan Light is a reference to maybe the most well known novel set in Capri, Norman Douglas' South Wind. Part travelogue, part literary and art history, James' book is difficult to define. It offers a series of vignettes of varying length connecting a veritable who's who of famous (and not-so-famous) literary and artistic expats. The minor players are offered as mere asides and provide a more complete sense of Capri's expat society. Pagan Light is anchored with biographical accounts of the little known novelist and poet, Jacques d'Adelswärd-Fersen and the artist Romain Brooks.

Adelswärd-Fersen flees Paris after his proclivities run afoul of the law. Interestingly it wasn't his sexual interest in teenage boys that was the problem, it was his use of them in his theatrical 'messes noires' (a supposed satanic ritual) to which he invited his friends. The details of this scandal would later be memorialized in his 1905 novel Messes Noires : Lord Lillian. An English translation of the novel, issued by Elysium Press, was published in 2005.

On Capri, Brooks was able to become an independent woman and present herself the way she was most comfortable. She cut her hair short and styled herself in trousers and jackets instead of dresses. She interacted within the society of lesbians of the time including Radclyffe Hall (author of the classic lesbian novel, The Well of Loneliness), Lady Una Troubridge (Hall's longtime lesbian partner), and American poet, Natalie Barney (Brooks' great love). Brooks is known for her portraits of important women in this lesbian circle as well as an early portrait of Jean Cocteau.

Adelswärd-Fersen and Brooks make for interesting subjects in that what we know of their lives is largely based on less than reliable depictions of them in their own and others writing. Adelswärd-Fersen's story is mostly known through The Exile of Capri, a roman à clef by Roger Peyrefitte, while Brooks' story largely comes from her own unpublished memoir as well as Compton Mackenzie's novel Extraordinary Women.

Ricardo Esposito, who runs the Capriot small press Edizioni La Conchiglia, sums up the importance of Capri nicely when he says, "Capri was an international laboratory for the avant-garde, a place where ideas were born, a new artistic vision, and given to the world." (p.288)

Friday, January 3, 2020

Ercole e Lica by Antonio Canova

Saturday, December 21, 2019

The Christmas Tree by Isabel Bolton (Mary Britton Miller)

|

| New York : Charles Scribner's Sons, 1949 |

Opening in the days leading up to Christmas 1945, Bolton presents the members of a family who are scattered across the country. Each person's inner dialogue is unique but all conclude that this Christmas will be challenging, particularly if everyone shows up.

Mrs. Danforth, or Hilly, is in New York with her 6-year-old grandson, Henry. She plans to give Henry that perfect Christmas that she remembers from her own childhood, including a tree with real candles.

Henry's mother, Anne is in Reno obtaining a divorce from Hilly's son, Larry. In support of the divorce, Hilly supplied a deposition confirming her son's behavior in the marriage. While still in Reno, Anne immediately marries Captain George Fletcher, a pilot during the war. Due to heavy snow, Anne and George are to arrive by train from Santa Fe.

Larry is also in the military but served stateside during the war. He lives in Washington DC and is gay. Christmas at his mother's house seems to be just the excuse he needs to end his current relationship with Jerry. Larry arrives by train, but not alone.

Novels from the 1940s and 50s typically have a Freudian slant in their explanations of relationships in general and gayness in particular—overly close relationship with the mother, absent father, etc. The Christmas Tree is no different. However, in this case it's not subtext. It is couched in the specificity of Anne's experience with analysis and her doctor's explanation of who's to blame for Larry's gayness. The explanation provided is the glue that holds the family together, for better or worse.

Bibliographies & Ratings: Cory (IV); Garde (P78**); Mattachine Review (IV); Young (345*)

Friday, December 6, 2019

Interior at Paddington by Lucian Freud

|

| Interior at Paddington (1951) Lucian Freud (German, English, 1922-2011) Oil on canvas 114.3 x 152.4 cm Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool UK |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)