|

| New York : Oxford University Press, 2018 |

2018 National Book Award

2019 Pulitzer Prize

Alain Locke was born into a Black Victorian family in Philadelphia in 1885. Stewart masterfully lays out the complexity of Locke's life through which he must balance his desire to be a successful black intellectual with his gayness.

After completing his education at Harvard where he was generally accepted, Locke has his first serious experience with racism while a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford when the scholars from the southern United States refuse to board in the same college as him and intentionally leave him out of group activities. Locke does make some friends though and escapes to mainland Europe, to Paris and Berlin, where his race is not an issue and he is free to explore his sexuality in a more open environment. His escape however proves detrimental to his scholarship and he fails to receive his degree from Oxford.

With the idea of completing his studies in Berlin, he asks his mother (with whom he maintained a close relationship) to join him there. When Archduke Ferdinand is shot, the Germans close the border and they are temporarily trapped. Although U.S. officials do work to evacuate them, due to their race, they are not a high priority. Once back in America, he takes a teaching position at Howard, but quickly realizes that without a PhD he won't achieve the standing and influence he desires. While on leave from Howard he completes his doctorate at Harvard. By this time, with the election of Woodrow Wilson—the first southern president elected since Reconstruction—race becomes more of a problem for Locke, particularly with segregated housing districts.

After completing his PhD, Locke decides to vacation in Europe and while visiting Berlin during the Weimar era, takes in some of the Modernist theater of the time. This presentation in the arts of the lives that the artists are living resonates with Locke and was a confirmation of the sort of artistic movement he envisioned for black Americans; what we would later know at the Harlem Renaissance.

Locke had been friends with several writers that are now known as part of the Harlem Renaissance; Claude McKay and Jean Toomer in particular. McKay frequently introduces Locke to new young writers, particularly young men, whom Locke encourages and mentors to a degree. The Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP, served as the primary outlet for these writers' work but simply accepted or denied work for publication instead of bringing new writers along with the sort of encouragement that Locke felt was necessary to create a movement. This was personal for Locke since he had experienced this himself with articles he submitted to the publication that didn't get him the attention from the editor that he felt he deserved.

By the time Locke returns from a trip to Europe and Egypt in 1924, Robert Kerlin has released Negro Poets and Their Poems in connection with The Opportunity, the publication of the National Urban League. This was the kind of thing that Locke had envisioned, a vehicle to promote the new writing in this movement of black writers. Charles Johnson, the editor at The Opportunity, like Locke, saw the connection between European modernism and African American poetry and theater and hoped to promote the arts within the pages of the magazine.

|

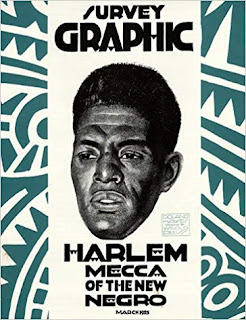

| 'The Harlem Number' Survey Graphic : March 1925 |

While Locke emphasized his vision for this new movement at the dinner, he emphasizes the importance of leaving old forms behind, thus alienating some the attendees. Jessie Redmon Fauset was the literary editor at The Crisis and had herself just published a novel in the style that Locke had so easily dismissed. Locke underestimated the power of Fauset and The Crisis in general however. The following day, newspaper articles describing the event omitted Johnson and Locke entirely, focusing primarily on Fauset and her new novel.

Although the dinner didn't get Locke and Johnson the sort of publicity they hoped, Paul U. Kellogg, the editor of Survey Graphic was in attendance and this led to the next opportunity for them to promote their envisioned movement. Each issue of the magazine focused deeply on a topic and Locke suggested to Kellogg the idea of an African American issue focused on the arts and featuring commentary from leading voices. Locke acted as silent editor of what would be later known as the Harlem Number. While it was a success at promoting the movement, Locke's involvement continued to be out of view.

Before the Harlem Number was published however, there were already thoughts of expanding the concept into a larger work. Albert Boni had recently started a publishing house with his brother and inquired about republishing the content of the magazine with new material in book form, also edited by Locke. This would become The New Negro: An Interpretation, published in 1925 and solidified Locke's critical role in promoting the authors and writings of what we now know as the Harlem Renaissance.

No comments:

Post a Comment